…. a map is always the start of something, not the end...

The Deepest Map

When I first started my GIS journey, one of the career paths that interested me was hydrography (it is still a secret dream). So when I came across The Deepest Map by Laura Tretheway in a bookstore a couple of months ago, I was intrigued. I really knew nothing about the growing push to map the oceans prior to starting this book. As Tretheway addresses in the book, many people including myself, have simply thought: what is there to map on the ocean floor? It turns out, at lot. The book follows the work of the Seabed 2030 initiative as well as the journey of a junior hyrdrographer aboard renowned explorer Victor Vescovo’s ship during his attempt to dive the deepest point in each of the five oceans (something I also wasn’t aware of). For a mapping and geography book, it does an excellent job of explaining the technology, history, and politics behind seafloor mapping.

All Maps Are Wrong…

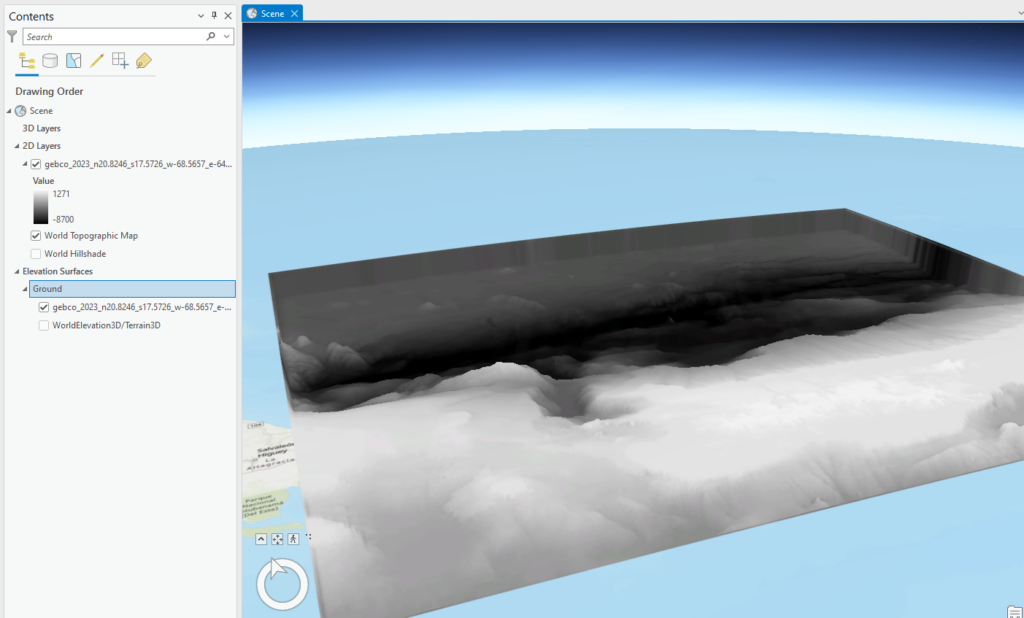

But the seafloor maps are really wrong. We all have in our minds a sense of the topography of the seafloor. For those of us in North America, the mid-Atlantic ridge dominates our awareness. It stands out in Google Maps, and gives us a false sense of how much of the ocean has actually been mapped. The issue is that up to today, only about 25% of the seafloor has been mapped, and many of the parts that have, have not been mapped when any degree of precision. A lot of our existing knowledge comes from low resolution satellite-derived gravity measurements. In an effort to get a sense of how much more interesting high-res seafloor maps are today, I went digging through ArcGIS Online’s Living Atlas. The following digital elevation model is from the coast of Japan and shows high-resolution details of the sea-floor:

A collaboration looking to change that is GEBCO/The Nippon Foundation and their Seafloor 2030 mission. Seafloor 2030 aims to map all of the worlds oceans by the year 2030. The Deepest Map looks at the history, current status, and achievability of this project. But awareness isn’t Seafloor 2030’s only mission. According to their website:

There are many benefits to having a complete map of our ocean. Knowing the seafloor’s shape is fundamental for understanding ocean circulation and climate models, resource management, tsunami forecasting and public safety, sediment transportation, environmental change, cable and pipeline routing, and much more.

Seafloor 2030 – https://seabed2030.org/our-mission/

You can even access their data for free:

https://seabed2030.org/our-product/

One of the most informative chapters is on the development of deep sea mining and the concern that the open ocean floor data from Seabed 2030 may aid deep sea mining companies. The Deepest Map addresses these concerns and analyzes the relationship between exploitation and exploration.

The Five Deeps

While the Seabed 2030 arc addresses the social, political, and technological aspects of ocean mapping, the book also follows Victor Vescovo’s Five Deeps mission which provides an in-depth look of how ocean mapping actually works and the realities behind mapping some of the world’s most remote places. The book follows Cassie Bongiovanni, a junior hydrographer right out of university who finds herself aboard the expedition ship, Pressure Drop. As the adventure progresses, we are exposed to how multi-beam sonar works and the realities of ocean mapping. Tretheway excels at both distilling a complex technology as well as making the process exciting to the reader. One can’t help but cheer for Bongiovanni, who begins the mission as somewhat of a mapping underdog, but ends up being a key component of Vescovo’s mission. As Tretheway notes, it was imperative to get the mapping right, so that someone else wouldn’t be able to claim they dove a deeper spot at a later time.

Not only did Bongiovanni’s mapping efforts help Vescovo’s mission, the data the mission collected was uploaded to Seabed 2030 and has been incorporated into the publicly available data.

Looking Forward and Looking Back

Besides the two main story arcs, the book also has fascinating chapters on unmanned robotic mapping, undersea archeology and crowd-sourced mapping. As someone who works in the geospatial world, even I was surprised by how many subject areas are covered through this lens of mapping.

And with Norway’s recent approval of deep sea mining, this book is more relevant than ever in order to understand the world’s last great frontier. I encourage you to get your hands on some Seafloor 2030 data, and visualize a place that has likely never been seen by human eyes.